On April 28, 1996, I should have been at the gates of the Port Arthur Historic Site, opposite where my fishing boat was on blocks having been salvaged after dragging its anchor and running aground on a reef in the bay.

Thirty-five people were killed that day at Port Arthur, and several of them near where I should have been working on my stranded boat. But I wasn’t there. I needed to sort out the exhaust on my old Valiant, to keep mobile. So I was safely 10km away in Nubeena under a car on a hoist while all those people were being killed.

All of us, who lived there then remember where we were that day, and I think we all have scars. I know some who have huge and irreparable damage. Most of the people killed were not from our region, or even our state – but we grieved. When anniversaries come up we grieve still. How much grief, then, arises from the school killings which have become so common in the United States. It must be unbearable.

What follows is an idea of how such gun violence in the US came about. When I first wrote about this a year or so ago, I ran it past my old political philosophy lecturer, David Coady, and he gave it a tick. So here is, somewhat modified, my essay on gun violence and the social contract.

The idea of the social contract was first raised (in western society) by the Englishman Thomas Hobbes, writing at the beginning of the 50-year political upheaval in Britain and Ireland which started with the English Civil War in the mid-17th century. However, it is probably best described by his countryman John Locke, writing 50 years later, after the final act of that upheaval – the so-called Glorious Bloodless Revolution.[1]

Writing in the aftermath of the political settlement of 1698, (and very much trying to justify what had just happened) Locke said that we give up our liberty to the state to the extent that the state will protect us from harm. And, you could add, provide us with the rule of law rather than that of force.

So, that is Locke’s concept of the relationship between the citizen and the state, his idea of the social contract. The state is something that protects us, but to which we are to some extent beholden – to which we have given up some liberty, in return for protection. Much later, the German Maximilian Weber gave a different definition, but one which can function as a coda to Locke. Weber said that one thing that defines the state is that it is the political entity which reserves the use of force to itself, and refuses it to anyone else. In other words, I give up some of my liberty to the state so that society can operate lawfully and I am protected. To this end, I allow that I cannot use force in personal relations but the state can do so to enforce the rule of law. This is a reasonable description of how nearly all liberal-democratic societies operate today – perhaps nearly all societies which have the rule of law.

Except the United States of America.

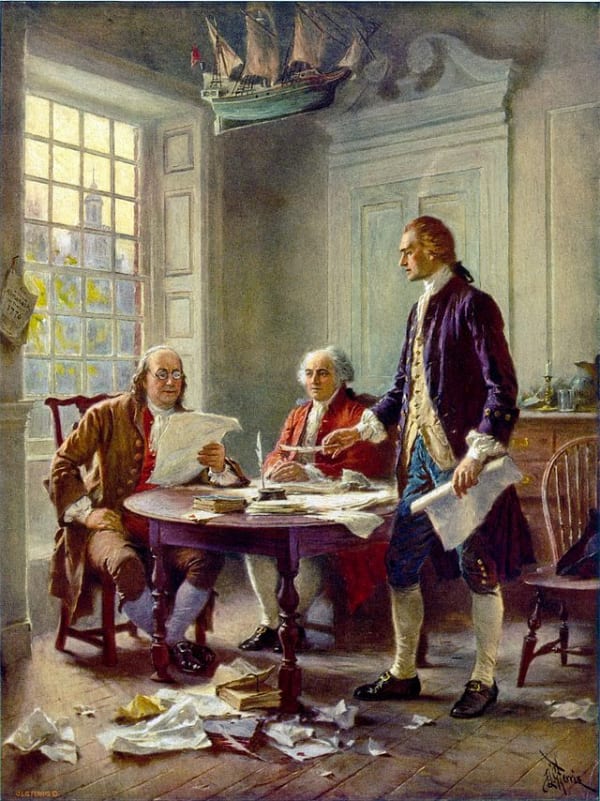

The American Declaration of Independence, signed in 1776 by the 13 rebelling colonies, states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their power from the consent of the Governed.” (My emphasis.)

So, in 1776, Thomas Jefferson and his colleagues were signing up, quite specifically, to a version of the social contract. They were possibly using Locke’s example from 75 years before, which was written to justify an earlier rebellion. They could well have been looking for historical or legal precedents; they were, after all, embarked on a desperate venture which could well have ended with their heads on a block. Or, more likely, in a noose, given that they were, on the whole, not aristocrats.[2]

The pursuit of the “unalienable right [to] . . . Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” could have led to the scaffold.

I have italicised “liberty” because the concept of liberty has become so valorised in the US, that it has overwhelmed any idea of the social contract as we have defined it, and also made any idea of communitarian effort “un-American”. This has become so to the extent that the idea of decent health-care funded by the government is ridiculed as communist. Again, this is a departure from the practice of nearly any other modern liberal democracy or, really, any law-run state.

One problem has become the Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America.[3] The Second Amendment states that, “A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” This is somewhat at variance with Locke and (especially) Weber’s idea of the state to start with, but the Second Amendment was also completely weaponised (literally) by a decision of the Supreme Court of the US in 1965. The court held that the words “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms” were absolute and had nothing to do with a Militia.

So now, the American government is the only one in the world of lawful states that does not, in effect, reserve to the government of the state the right to bear arms and to use force. If you may “bear arms”, presumably you can use them, and this has been the feeling of many American courts – using a gun is not prima facie a bad thing to do. How can it be if the Constitution allows it?

We have seen the consequences.

. . .

An extraordinary fact is that the greatest cause of death in children in the US is from guns. That is a serious, absolutely true statement that I cannot believe I just wrote. We have a very young man killing 19 children, we have white supremacists killing black people in numbers, and we have the spectacle of rich, middle-class lawyers waving guns around that could kill hundreds in minutes because they suggest that they feel threatened by a Black Lives Matter march going past their house.

I don’t think they were really threatened, but they needed to wave their outrageously, ludicrously, powerful machine guns about because black people were walking past their mansion.

Yes, the whole thing is connected to racism. African-American protests have been met by pro-Trump groups who brandish the commercial equivalent of an AK-47 assault rifle, the AR-15. The protestors have reverted to the older Russian weapon of resistance, the petrol bomb or Molotov cocktail.

Mikhail T Kalashnikov conceived and created his assault rifle while recovering from wounds incurred during World War II. AK-47 stands for Automatic Kalashnikov 1947. In Russia, the war was known as The Great Patriotic War and it had cost something like 20 million lives. Mikhail Timoreyevich (to use his patronymic, as he would have usually been known) wanted to put more firepower into the hands of an infantryman; ie, he did not see his rifle as a civilian weapon. But, just as George Orwell saw the Winchester repeating rifle as a medium for creating social equality[4] – because it was affordable – so too did people find Kalashnikov’s cheap and reliable assault rifle a weapon for revolutionary change.

But now we have AK-47 equivalents and even more powerful machine guns on the streets of America. No other government in the world – fascist, communist, socialist, social-democratic or liberal-democratic; no-one – would contemplate the idea of people on the streets waving around machine guns. But in the US it can happen because the idea of liberty has been completely valorised, and guns have become enshrined as a totem of that liberty and that valorisation.

. . .

That this happens is a complete repudiation of any idea of the social contract that the Founding Fathers signed up to. In fact, it is a complete repudiation of any idea of a cohesive society. It is a reversion to one interpretation of Old Testament morality and world-view, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth[5],” and a tribal “we against them” ethos. We are good, Philistines are bad, and as for Canaanites!

This allows the intrusion of the idea that any central government is irrelevant: that your tribe is all that matters and that your personal protection is in your own hands. It strikes me that the tribes of America are multiplying and fracturing, and that, to a certain extent, local governments and their police forces have signed up to their self-identified tribe – which are not black. Tribal law enforcement (sometimes brutal) follows, and the opposing tribe reacts.

What is depressing is that re-reading a brilliant account of the 1968 presidential campaign (which becomes a time capsule of America in that extraordinary year), I find that de facto segregation, in both the north and the south has really not changed. In the north, cities like St Louis, Cleveland and Chicago – cities with great civic institutions such as universities and symphony orchestras – are basically segregated into black and white districts. When we get to the south, Atlanta, New Orleans and even the capital, Washington DC, are the same, if not worse. I read, in this 1968 account, about the same racial problems but find the gun violence exponentially worse in 2022. And the racial oppression problems, too, seem even worse; in terms of voter suppression and, especially, in terms of police shootings.

What would we feel if people were throwing Molotov cocktails on the streets of Perth? That just could not happen, could it? Well, the weeping sore on American society is, obviously, racism and the legacy of the slave trade. The incarceration rate of young Aboriginal people is far higher in Western Australia than that of young African-Americans in Minnesota (where George Floyd was killed) or anywhere else in the US, yet no one is throwing bombs down Hay Street. This could be because we have not fractured as much as American society, aided by the fact that guns are banned. But perhaps we should work out why so many Aboriginal kids are in prison before we start throwing brick-bats at the US, or before people start throwing bricks on the streets of our cities.

I remember the Port Arthur massacre and the effect on my little community. I can’t imagine what the parents of the victims of the school-massacres in the US go through. It is beyond my imagination.

The lesson I took from the Port Arthur massacre (quite arbitrarily, and desperately grasping for meaning at the time) was that social cohesion is a philosophical “good”; something worthwhile in itself. I hold to that 26 years later. And I hope that we can get back to an idea of an inclusive society that welcomes refugees and respects the needs of First Nation people. Rather than a society that rejects the “other”, as it is now called. I do hope.

The great boxer Jeff Fenech, who had just won a world title but taken a fearful beating at the same time, did not tell the crowd, “I am the greatest,” or even, “I beat the prick.” Instead, he gave us the immortal words, “I love youse all.”

It was the most gracious and magnanimous victory speech ever given.

When politicians and other “important” people are spinning their crap, try to remember Mr Fenech’s words, “I love youse all,” and the circumstances in which he said them. I try to remember it all the time. It helps.

NOTES:

[1] Not glorious – a very cleverly staged affair; nor bloodless – people got killed; nor a revolution, more of a coup.

[2] Aristocrats have their heads cut off; commoners are hanged.

[3] The amendments form a coda to the Constitution and are collectively called the Bill of Rights.

[4] It is strange, but true, that the socialist Orwell saw the Wild West as a free society, where power was in the hands of the people by the availability of the Winchester repeating rifle and the Colt revolver. Most historical observers would see the Wild West as anarchic, and Orwell’s ideas as romantic in the extreme.

[5] The “eye for an eye’ idea as being inherent in Old Testament theology, and inferior to our Christian “love God and thy neighbour” may have been a product of casual anti-Semitism in post-war Australia.

James Parker is a Tasmanian historian (but with deep connections to Sydney), who writes and talks on mainly colonial subjects – especially convicts, women and the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.