It’s easy to be dismissive of certain trends, like the fads and phenomena that preach a return to all things natural and organic. From interest in caveman diets to curing cancer with food, the notion that mother (nature) knows best is an alluring ideology. The medical advancements that the modern world has gifted us deserve due credit, but the most curious element of these movements involves a switch, so to speak, from viewing our ailments as mutations in need of correction by science, and rather considering pain and disease as the consequence of parting from our natural ways. The controversy behind this mental flip is its allocation of personal responsibility over pain and health, and for this very reason, practices such as the Alexander Technique have never quite earnt strict scientific credibility.

We become no more acutely aware of our fragile humanity and connection to the natural world when something, once thought inherent to our very selves, is taken away from us. As an early 1900s professional reciter, Frederick Matthias Alexander felt the impact of losing his voice not just as an inconvenience for work, but as an artist losing his tools. In an era void of microphones, and when ‘professional reciter’ was a viable career pathway, Alexander’s passion for Shakespeare, theatre and poetry lead him to a career dependent on his voice that would come to fail him, and ultimately define him.

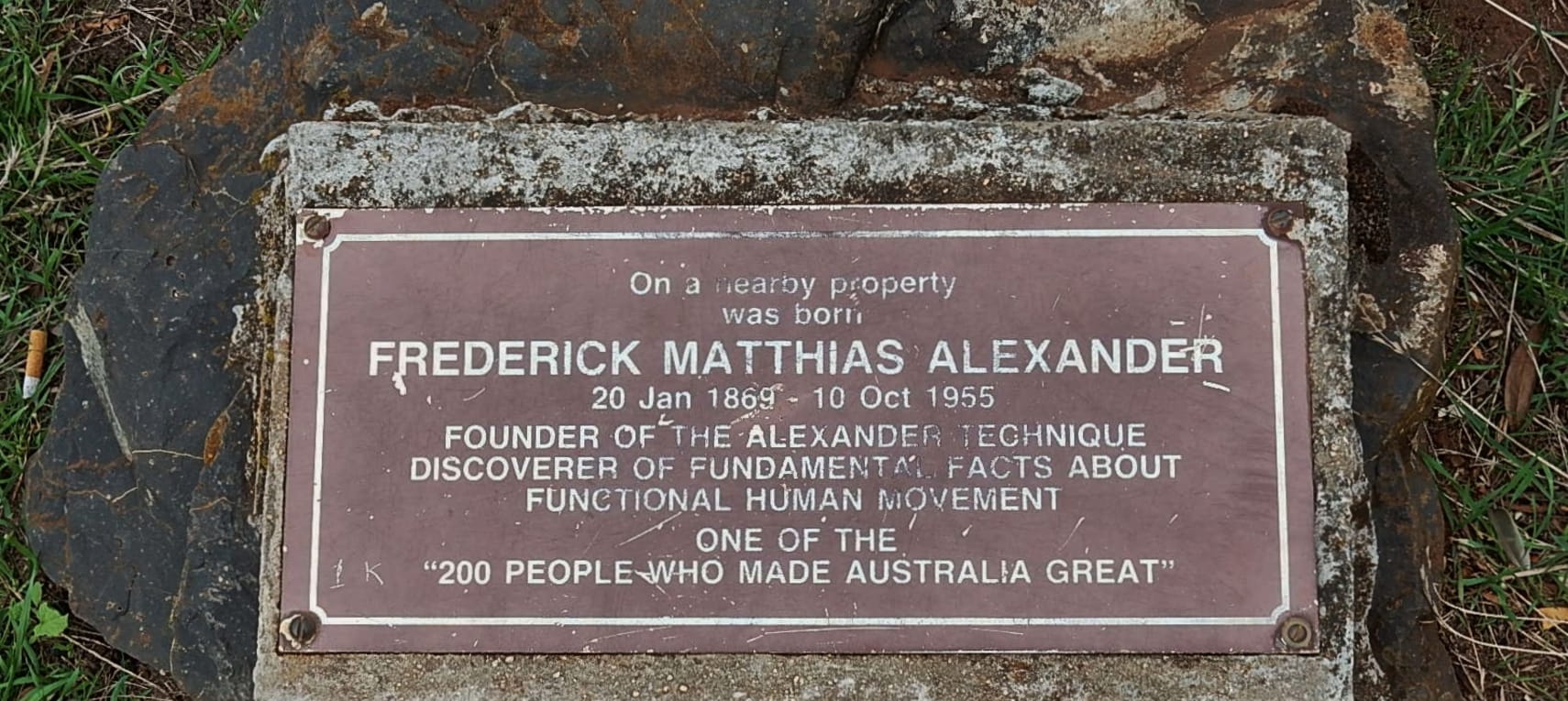

Born on a farm north of the Inglis River and the present-day town of Wynyard, Alexander was born premature and suffered respiratory problems that his 9 other siblings did not. His father, a blacksmith, ran a deeply devout Protestant household that valued honest hard work and strict discipline, contrasting (not coincidently) their convict ancestry that Alexander himself always worked hard to hide. With this devotion to the church (and a realistic view of his future on the farm as an asthmatic), Alexander’s mother sent him to Sunday School and later the local government school to gain an education. Here he proved to be precocious, sensitive and exuberant; all excellent attributes of a budding artist, but not-so valued qualities in a late eighteen-hundreds classroom. Saved not for the first time by the compassion of another, Alexander’s teacher, a Scotsman named Robert Robertson, excused the young student from typical school attendance and mentored him by evening. In addition to his education Roberson gifted Alexander with a love for the arts, and between the pillars of support provided by his teacher at school and mother at home, Alexander recalled an idyllic childhood.

The time between his youth and pursuit of a thespian profession appears equally pleasant. Considering he had only been promised a minor roll within the offices of the Mouth Bischoff Tin Mining Company of Waratah, it took Alexander only two weeks to be promoted to the position of ‘permanent official’, and three years to save a remarkable £500 sum. Despite all his successes, Alexander was never safe from what he described as ‘violent internal pains’ and symptoms we’d commonly recognise today as chronic asthma. These pains would come to plague him later in life. By 1889, Alexander did what any successfully comfortable businessman with infrequent attacks on his health would do: He packed up and moved to Melbourne to pursue a career in the arts.

It must be noted that a great majority of what we know about Alexander’s early years come from his own auto-biographical essays, but an objective outline of his personality appears rather clear. He was proud, independent and industrious, with the incredible ability to single-mindedly apply himself to achieve often ambitious goals. He always described himself as agnostic, but generously credited his religious upbringing as responsible for his deep sense self-discipline and personal responsibility that would later prove pivotal. A beautiful account by author and historian Michael Bloch perfectly and poetically provides insight into the world Alexander was about to enter:

He must have had marked feelings of being an outsider – for Australians were the outsiders of the British Empire, Tasmanians were the outsiders of Australia, and those from the north-west of the island were the outsiders of Tasmania.

Fast forwarding to 1891, Alexander has experienced Melbourne’s economic boom and subsequent depression that that mirrors his own fluctuating health. Years of odd jobs and finally frequent roles in dramatic recitals are overshadowed by growing hoarseness in his voice, audible gasping for air and ultimately the loss of his speech. The doctors in his mind were of no use, prescribing rest and refraining from harmful activities that may involve speaking loudly for long periods of time, like say, reciting poetry in front of large audiences. In an era where mercury was used to cure syphilis and radium water for arthritis, Alexander’s thought-process must be credited as truly remarkable for his time. For Alexander the problem, it seemed, was him.

So, what is the Alexander Technique? With a self-titled practice prevailing beyond the nineteen-hundreds, by now we know Alexander’s story must end well. With the aid of mirrors Alexander began to correct his posture and the habit of tightening his neck while projecting his voice. He soon discovered the act of simultaneously pulling his head back and chin forwards put significant pressure on his throat and voice box. Correcting this and unlearning what he considered unnatural habits performed miracles: Not only did his voice return, but the asthma that had plagued him since birth seemed to have disappeared.

Through this Alexander had tapped into an age-old notion that our bodies require total harmony; that correcting bad habits and posture in one area provides benefits for the whole body and soul. Setting up practice in Melbourne, Sydney and finally London in 1904, the core concept resonated with people then just as it resonates to many of us now.

As Forty South's newest employee, Ella moved to Hobart after completing a BA of Media at Adelaide University, South Australia. While working and studying in the United Kingdom she discovered her passion for publishing and people, writing copy for regional cookbooks in the UK and abroad.