December 8, 1923, saw the first Antarctic blue whale killed in the Ross Sea by the steam whale catcher Star II. It was towed to the factory ship Sir James Clark Ross and rendered down into 80 barrels of oil. It was the first of many thousands in a slaughter that brought the world’s blue whale population to its knees.

Aboard the Ross, and witnessing the first kill, were twelve young men recruited in Tasmania by the Norwegian Ross Sea Whaling Company. Ross called into Hobart in November 1923 to pick up the young men, fresh water, coal and the last fresh vegetables the ship’s company would see for several months. She returned to Europe in 1924, via Hobart, having proved that Antarctic whaling could be profitable, and so sealing the fate of the largest mammals ever to have evolved on Earth.

The young men – the “Tassie whale boys” as they called themselves – were as typical a group of young men as could be found anywhere. All were in their 20s and yearning for adventure. Some left secure jobs to go whaling; others were victims of Hobart’s flagging economy. Along the way, they experienced the most intense cold on Earth, the fiercest storms thrown up by the Furious Fifties and Screaming Sixties, the agonising beauty of Antarctic summers, and the truly gruesome business of turning whales into oil.

The Ross returned to Hobart in November 1924, having made a number of modifications to the deck and hauling gear to make blubber handling more efficient. She slipped into the River Derwent, anchored midstream, and less than six hours later was on her way again. Another group of Tassie whale boys had joined the ship, with two of them making a second trip.

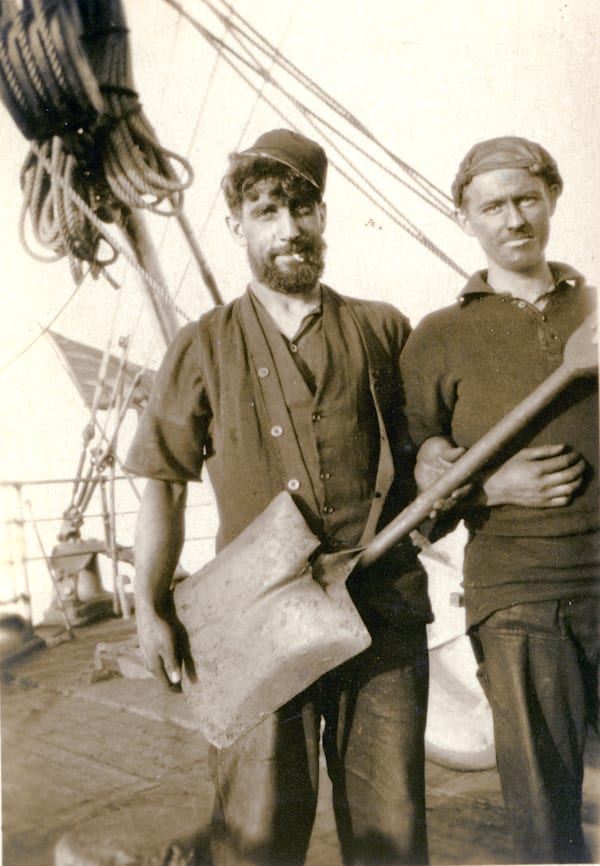

Photo courtesy of the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, Hudson Collection.

The Ross returned to Antarctica again in 1925 but this time gave Hobart a miss because the Commonwealth Government’s new Lighthouses Act specifically penalised whale factory ships which passed by the Derwent Light.

In 1926, after the Act’s amendment, a newly formed Norwegian company, Polaris Whaling of Larvik, sent its flagship to Hobart en route for the deep south. The NT Nielsen-Alonso and her five catchers called Hobart home for the next five summers until 1931, when the oil market collapsed and Norway’s whaling barons gave the whales a year’s respite.

Altogether 132 young Tasmanian men went whaling between 1923 and 1931, some making several trips. During this time their factory ships processed 5,000 whales and made a fortune for the company.

The diaries of several of the young men have survived and in them we catch a glimpse of what life was like aboard the early Antarctic steam whalers. Few of the boys had much idea of what to expect when they signed up. Their contracts were written in Norwegian, which none could understand, but even if they could it would have made little difference. Some saw themselves signing up for a Boys’ Own Annual adventure; others thought they would have a wonderful holiday amid the ice, penguins and whales. Instead, they found 18 to 20-hour days of exhausting and back-breaking work in freezing cold, and in the most dangerous workplace imaginable.

The diaries tell of the boys’ feelings about their fellows, the harsh Norwegian bo’sun who made their lives hell, the stoicism of the officers, the wretchedness of the food that led them near to mutiny, and the pitiful pay for their hard labour.

They also tell of their feelings about the Antarctic summer when the sun’s midnight catenation low over the horizon sprinkled the world with more colours than could be imagined.

The young Tasmanian men earned the respect of the finest Norwegian sea captain of the day and did themselves, their state and their young nation proud. This was never more obvious than when the captain called for a party of volunteers on Christmas Day, 1923, to build an emergency food cache on the sea ice to provide a survival chance for the crew of an overdue catcher. First in line for this cold and hazardous work were the Tassie boys. The missing catcher turned up after a few days, and the boys’ readiness for hard work endeared them to the Captain’s heart.

The Mercury newspaper appointed a special correspondent from amongst the young men on the eight annual whaling expeditions that departed from Hobart. The first to fill the role did so with distinction. Alan Villiers was just 20 years old and a proof-reader at The Mercury when he joined up in 1923. His 15 articles about the trip were serialised on his return and were snapped up by Hobart’s people, hungry for knowledge about Antarctic adventure. The newspaper syndicated his articles around Australia, earning him £1,500 – a huge sum for such a young man. This launched him on a literary career that spanned 40 books dealing with the graceful age of sail and other maritime topics.

The whale boys rarely thought about the cruelty of whaling, or the damage to whale stocks done by the catchers’ rapaciousness, though in later years they reflected dolefully on the part they had played in the near extinction of the largest animals on Earth.

Photo courtesy of the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, Morrison collection.

What shines through the diaries are descriptions of filthy decks, rotten food and the stench of putrefying whales intermingled with irrepressible youthful optimism and a desire to live life to the full. The boys’ unbridled spirit of adventure got them through times when the marrow froze in their bones and frostbite blackened their fingers. It helped them when an iceberg almost got the better of them and they were called to lifeboat stations. It helped them celebrate Christmas like never before when so far from home and loved ones. There wasn’t a single boy leaving Hobart who didn’t return as a man.

Too soon after their whaling days were over the world was gripped by war. Most of the young men signed up for service. Several were decorated for bravery in action, and a few lost their lives. Harry Brownell, a young naval officer who’d been whaling in 1927-1928, led the first group of troop-landing craft ashore at Dieppe in Operation Jubilee (a 1942 dress-rehearsal for the later D-Day landings), only for a German bomb to score a direct hit on his vessel. His body was never found. Alan Villiers, whose writing career was built on his Mercury essays in 1923, commanded a similar landing craft at D-Day, and was awarded a DSC for his actions. He saw service as a naval officer in Asia in a distinguished wartime career. Jack Ratten, who was only 16 when he went whaling in 1929-1930, was awarded a DFC for leading a flight of spitfires and destroying four or five enemy aircraft. Tragically he died a few months before war’s end following an accident in his aircraft. He was the first Australian to lead an RAF fighter wing. Another 16-year old when he went whaling, Paul Simmons (1926-1927), found himself stranded behind enemy lines in Papua New Guinea and fought a long, bloody guerrilla war under appalling conditions. He returned home to a hero’s welcome but shunned publicity because he was sickened by what human beings can do to one another.

The whale boys saw Antarctica at its pristine best. Their diaries reveal an Antarctica quite unlike the one we know today in which the sight of a blue whale is remarkable. The activities in which the boys engaged were gruesome and of course, as we now see it, deeply regrettable. But the norms of the time were different from ours today; the shock and revulsion we feel about the awful tasks they undertook back then are separated by almost a century from our modern perception of whaling as a barbarous act and we shouldn’t judge them harshly. In time they became bankers, shopkeepers, firemen, policemen, and teachers. They ran businesses, built railways and roads, mined gold and copper, smelted zinc, caught fish, built family farms, grew apples, made jam, and generally created a better society. They became husbands, fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers, and their lines live on in Tasmania to this day.

Hudson collection, photo courtesy of Maritime Museum of Tasmania

. . .

Michael Stoddart was formerly chief scientist of Australia’s Antarctic program and director of the University of Tasmania’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies. He is a biologist and author of Adam’s Nose, and the Making of Humankind, published in 2015 by Imperial College Press, London. He is now a researcher at the Maritime Museum of Tasmania.

The names of the 132 young Tasmanian men who went whaling are preserved in the archives of the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Canberra, and their records form the basis for Michael Stoddart’s latest book, Tassie’s Whale Boys, upon which this article is based. The book will be published by Forty South and released in February 2017.

Michael was born in Scotland and is a triple graduate of the University of Aberdeen. Settling in Australia in 1985 he held academic and administrative positions in Tasmania and New South Wales, including ten years as Chief Scientist of Australia’s Antarctic program. As the first director of the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies he oversaw the Institute’s development on Prince’s Wharf. Michael is a researcher at the Maritime Museum of Tasmania where he is completing an account of the sinking of Blythe Star off Tasmania’s south west in 1973, and challenging the controversial decision of the Court of Inquiry.