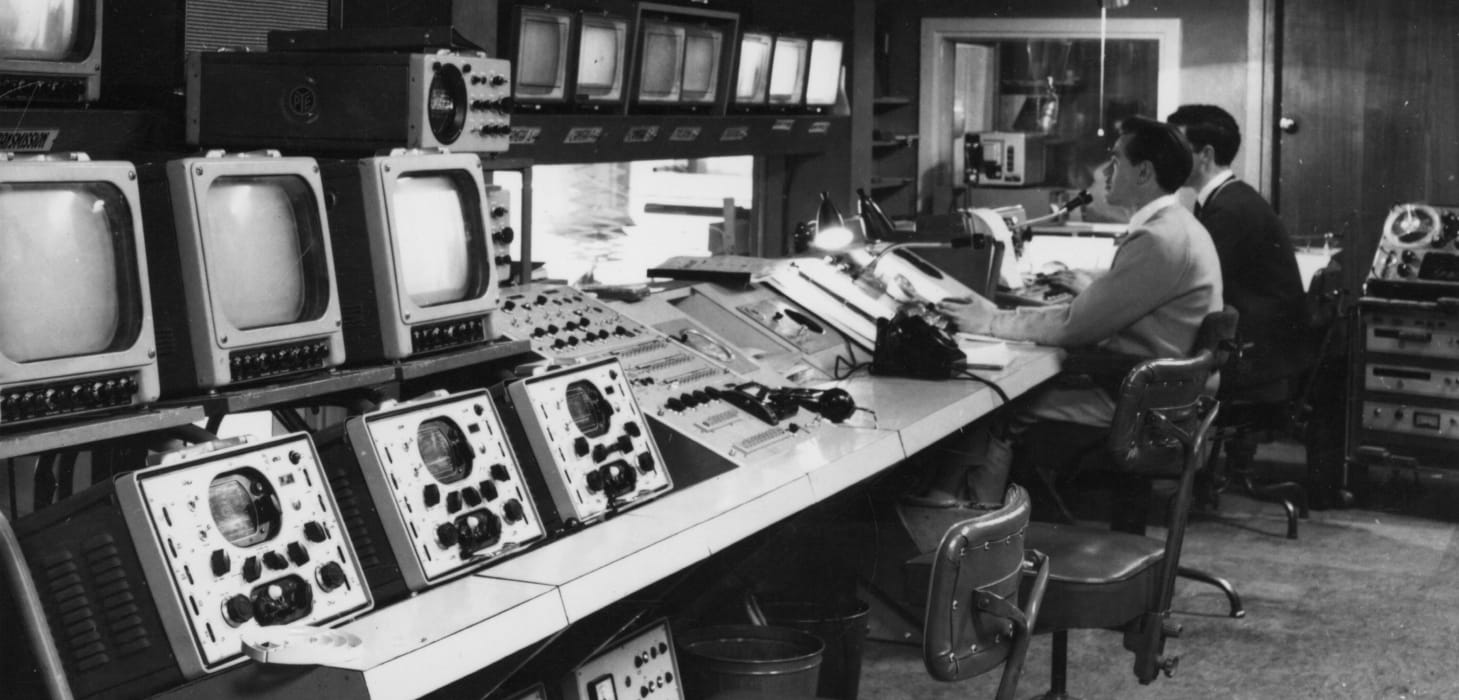

Photographs from the BRUCE WOODS collection

It depends on which clock you’re looking at, but for Tasmanians television has now been around for half a century.

It’s a long journey, as yet unfinished, and every step an argument about the worth of what we watch. But it is the technology of television that has defined, even dictated, those programs we’ve seen. It is the technology that is both the comfort and the curse.

Television is an invention of the many, dating back to 1831 and discoveries about electro magnetics. The word itself was coined by Constantin Perskyi at a conference on electricity in Paris in 1900, yet it was 1929 before such a device flickered to life in John Logie Baird’s studio in London. His screen was half the size of that of a smartphone today.

US consumers got their first look at TV a decade later in an exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, described by RCA as “radio’s newest contribution to home entertainment”. The technology took decades of toil by Bell, Edison, Zworkin, Farnsworth, Varian and Goldmark, among many, but their vision became our television, their work our entertainment.

Australia had to wait to see those developments. It was 1956, in time for the Melbourne Olympics, that television became available here, by which time about three-quarters of US homes already had TVs.

Importantly, the key technical blocks were in place. The camera tube captured images in electronic form, coaxial cable made it possible to send those signals by wire, and VHF waves put it into homes. TV sets – small screens in clunky boxes back then – were able to decode and display the signal. Television had arrived.

Tasmania’s first station opened on May 23, 1960. The launch of TVT6, in the suburb of New Town, capped months of excitement. After a speech by the governor, audiences – many viewing unbought TVs in shop windows – saw a news broadcast, followed by episodes of Dennis The Menace and I Love Lucy.

TVT even flicked a quick salute to its sole competitor for viewer eyeballs; the ABC’s Channel 2 would open two weeks later.

The launch meant that every Australian state now had at least one television station. At a national level, it was a triumph of technology, but for individual viewers, something of an emotional moment. Television linked households and brought the world into our living rooms. It did what radio had done for our grandparents, but it did it much better.

Crucially, the newly minted Channel Six was independent, without direct affiliation to the emerging Seven and Nine networks, and sourced content anywhere it chose. The result was a richly endowed line-up of imported programs.

More, if you wanted to do some TV advertising, this was the only game in town and commanded high prices for commercial time. In the second full year of operation, remarkably, its directors reported a profit of £60,000, more than $1 million in today’s money.

A lack of recording technology required live, local content and TVT6 invested in a creative output that is staggering by today’s standards. Kids’ programs like the Channel Sixers and the Junior Sports Show, then, later, daytime chat shows, a cooking presentation with Elizabeth Godfrey, and a current affairs program introduced Graeme Smith and later Trevor Sutton.

By the early 1970s, a crew regularly covered the football match of the day, for replay and endless dissection on a Sunday sports panel program.

Even then, the innards of television equipment were often valves, demanding constant tinkering. TVT6 kept 14 technicians busy, among them Bruce Woods, who arrived in 1968. Woods, one of those gifted humans who can diagnose technical issues at 20 paces, remains highly regarded, even in retirement being asked to work on various TV projects.

“A huge amount of content was locally made,” he recalls. “We techs needed to spend 30 minutes getting the cameras warmed up and aligned before work could start on making TV commercials.” In the studio, a crew of cameramen, lighting techs and a floor manager awaited. Adjacent, a canteen ran almost non-stop, and upstairs staff managed sales, scheduling, program buying, accounting and the all-important pay cheques. Elsewhere, news footage was being shot on film, requiring another cadre of processors and editors, journalists and producers, all under the guidance of the news editor. At its peak, TVT6 had a full-time staff of more than 100 people.

National ads, meanwhile, like much of TVT’s programming, came as 16mm film. That medium, a standard for TV’s formative years, was labour-intensive.

A small assembly line, mostly women, cut film programs into sections with an “academy” (numerical countdown) between each. Advertisements would be played in the gaps. Other hands wound the spools onto “telecine” machines – projectors at which a basic camera was aimed. After airing, all the film went back to the assembly line to be reconstituted into its original form.

Similarly, commercials were spliced into a single reel, and in the order to which they would go to air. If, as often happened, there were too few copies of the same commercial for a nightly schedule, that reel of commercials had to be recut and respliced, by hand, during the night’s programming.

During the time the station was on air, yet another pair of hands had control. The switcher selected from picture sources – studio, film or videotape – a complex task because media like film and video require time to get up to operational speed. That lag before a picture could be put to air (three seconds for film and seven for video) demanded deft hands and a constant eye on the clock. And occasional shouting.

For those watching TVT’s programs, change was coming. Pent-up demand for television had brought rapid take-up of sets in Tasmania – faster than any other state – despite prices which began at an eye-watering £200-plus pounds. In 1960, that was about an average annual wage. But inside a decade, the consumer landscape changed like that at the studio itself, with picture quality improving and prices falling steeply.

Across town, the ABC had also invested in local production, particularly news offshoots and documentaries. A succession of local current affairs programs followed the 7pm news every weeknight. Up north, TNT9 aired its own smaller but significant production output.

In Hobart as around the world, the arrival of VR 1000, and later AVR 1, videotape machines marked a tectonic shift in TV operations. The Ampex quadruplex videotape recorder was technologically seductive: it delivered much improved visual quality, and enabled stations for the first time to easily record their own programs and commercials.

However, while people like Bruce Woods were busy, film’s days were numbered.

As Australia moved towards colour TV in 1975, Channel Six invested in a raft of updated equipment. One item was the ACR 25 videotape machine: in 10 seconds, it could select and play a commercial from a bank, eject it and reload the next commercial. And it did so with nearly 100 per cent reliability.

Today, Woods reflects that videotape technology, which shifted from valves to transistors and then to computer chips, established benchmarks for high resolution pictures and automatic operation. “In fact, videotape foreshadowed digital recording on computers, now the industry standard,” he says.

A new world was coming, and fast. Satellites, showing real-time images from around the world, had been proven in 1962. Strongly advocated by Kerry Packer’s Nine Network by the 1980s, satellite-linked networks were unstoppable. Closed captioning, VHS home recording, then DVD players and digital video recorders like TiVo … the technology just kept coming.

In 1982, two decades after a ballsy, independent start in life, TVT6 was bought by Launceston company ENT, owner of TNT9, and the newly branded TAS TV maintained a common schedule for six years. In October 1994, the Hobart station was sold to regional network WIN Corporation, and TAS TV became WIN Television. Bruce Woods, who stayed on to help with the transition, remained with the company for nearly 10 years.

Left to right: Arriflex 16mm film camera, used for news; PYE Vidicon studio camera (B&W), one of TVT’s first cameras; Sony BVP 300 news camera, Australia’s first, replaced film cameras in news gathering; Sony BVP 360 studio camera, the second generation colour studio camera. The cleverly designed pedestal base is a holdover from the studio of the 1960s.

It’s considered that today’s television delivers better images, higher production values and slicker presentation. The machines have delivered what we asked of them: faster, cheaper, smaller. But technological change is unforgiving, devoid of loyalty and stripped of memory. The imperatives that created television in the past now force the future. A current model sees smartphones and tablets as receivers, and the internet as the distribution channel. While computers and television have converged, more channels have emerged, so TV’s audiences, revenues and delivery systems are being sliced and diced every which way.

Today in Tasmania, ABC and WIN – one public broadcaster and one commercial – maintain their separate schedules and separate identities. But their separate programs emerge every day from a single television control centre, 1000 kilometres away from Hobart, at Ingleburn in Sydney’s southwest.

The ABC, which has occupied a custom-designed radio and television production centre in Hobart since the 1980s, halted local television production 12 months ago, citing the cost of maintaining a dedicated staff in a small state.

And in New Town, Bruce Woods looks around the former TVT6, now a hollow shell. At its core, the large television studio is silent, its production suites empty, its human heart faded to black. “Yes,” he says, “there’s now a much more efficient way of delivering television programs …”

He leaves the thought unfinished.

Mike Kerr is a writer, journalist, cartoonist, radio producer and occasional comedian at www.theworldaccordingtokerr.com.au