We were talking as the sun burst out from behind a pack of clouds. Her dark curls had been garlanded by the curling yellow leaves of a stunted fig.

“So I took off,” she continued. “I went for a drive in the Pajero, and came home a month later. I’d circumnavigated the island. No plan, more than a thousand kilometres. Camped in all sorts of corners, saw parts of Tassie I didn’t know existed. Met strangers, slept on their couches. Or on the carpets, like a spinster from a South American novel.”

I’d done something similar once, although my itinerary hadn’t been entirely improvised. I lived in the north; I’d been invited to a party on the east coast; then I had a radio interview in Hobart; finally, I was booked for a festival in the west. There was a beautiful sunset just before I arrived back at home, and I decided to camp at a beach on Bass Strait because I wasn’t quite ready to be back within walls.

Later I had a crack at living out of my car. In truth I hadn’t often forced myself to fold into the back of that vehicle – a 1992 Ford Laser – but sometimes I had, when I couldn’t find a better spot. Better places were easy enough to find though. Tent, hut, yacht: I’d ended up resting my head somewhere different almost every night. It offered a certain thrill. Until, to no-one’s surprise, the Laser broke down. Living out of your car is fun until it doesn’t go. Then it just becomes a very small and inconveniently shaped house.

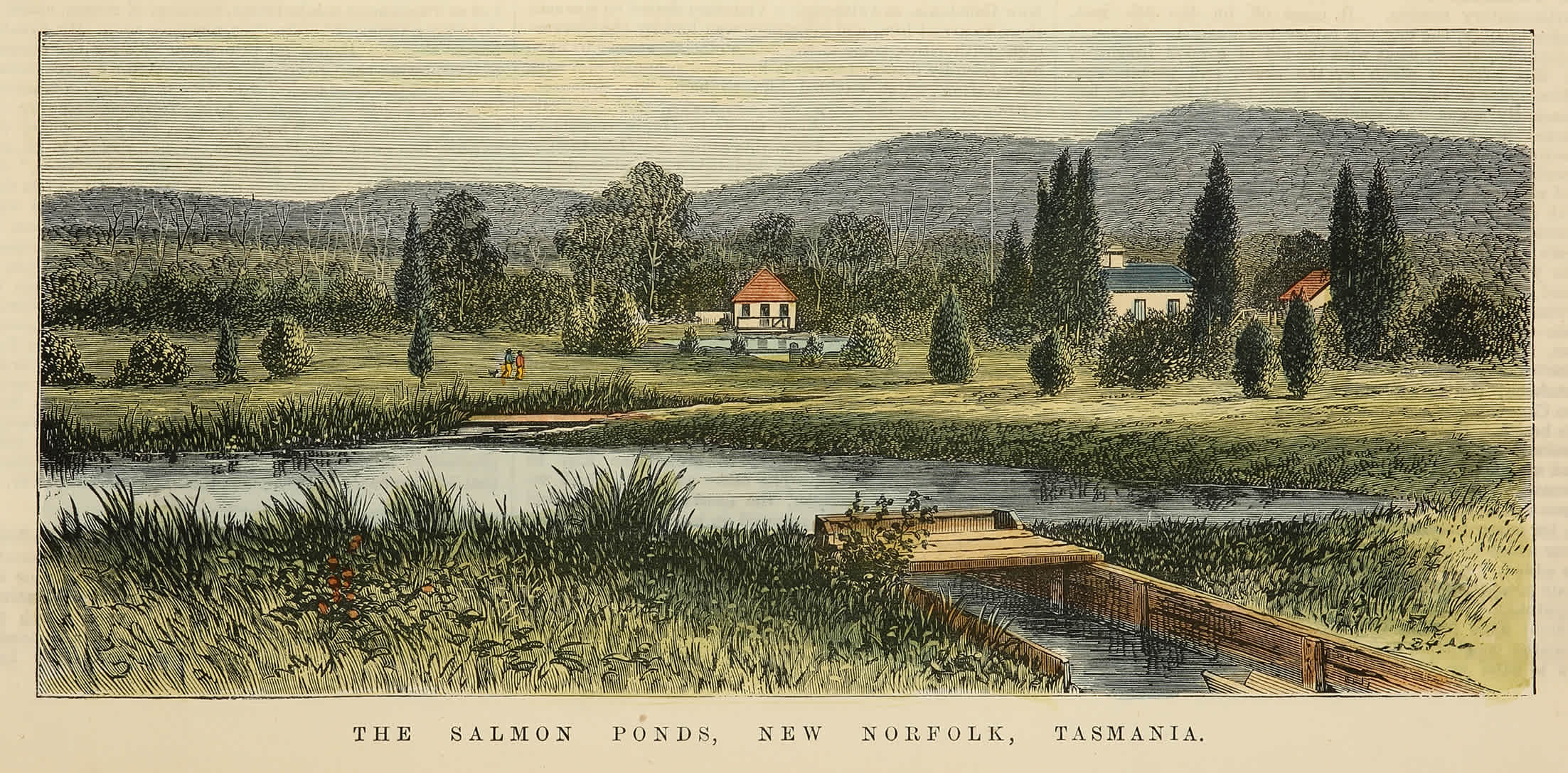

“The addictive element is mobility,” I suggested. Her eyes were fixed on a cohort of ducks that came from behind the gums and skidded onto the pond, but I knew she was listening. We had met in the summer, in the shed of a mutual stranger, at an impromptu party in which sea chanties had been the predominant entertainment. Some hours later, in the middle of a typical backroad, on one of those scraps of land that dangle so perilously in southern waters, we had chastely kissed each other farewell. The stars had been swirling slowly, an occasional spark dislodging itself and fizzling out in the darkness.

A pause. “Well,” she answered firmly. “It’s not as if we have anywhere to remain motionless.”

These days, she was staying in a squat while I was living temporarily in a room offered by a generous friend. We had both chosen paths that took us to the edges of things, away from a fixed address. Perhaps by now we could have saved up money and bought a house; others have, making it seem like no exceptional achievement.

Now she quoted a writer who described our lifestyles as a condition of “precarity” – that is, the precariousness that has become normalised in our lifetimes, as the systems around us start to crack and threaten to unravel. “Look at how we’ve had to cobble together a livelihood,” she said. “Or rather, livelihoods. We believe in patchworks, not progress. There is no goal. No narrative arc.”

I smiled. “Living out of my car, I learned to make home country out of the whole island,” I explained. So the surface of Tasmania was a patchwork of places I could claim as my own, albeit sometimes not legally. But I knew that these could easily be closed off.

. . .

As we spoke, a blackberry cane had scraped her shin and a little cut had formed. All around us the blackberries colonised bushland with alacrity. Recklessly, luckily. I’d hacked at it ineffectually with a brushcutter earlier in the summer. There had been sparks over the paddocks then, and a pall of black smoke rising from behind the dam. One night, as those bushfires burned nearby, I pulled up at home and heard ugly sounds from beneath the bonnet. It was a minor issue in the end, but for a moment I thought that the engine had gone. I had a sleepless night imagining I would be caught on the property, a blaze around me, unable to evacuate myself because yet again my car had conked out.

“I don’t much believe in the future. Or rather, I can’t seem to form a relationship with it,” she murmured. Would either of us buy a block of land that may well burn in the summers to come? Could she bear a child without knowing what sort of world they might grow into? Why store up treasures? How have faith? How learn to love?

What we had cultivated instead was a vicious instinct for independence, in which ties could quickly be severed, possessions gathered and stowed away or sold. Of all the skills we’d ever learned, movement was the most useful. Movement had become a master. If disturbance was going to occur regularly, we’d decided, we would ensure we could detach ourselves quickly from what was being swept away. In the process, we had traded many good things in exchange for freedom to move, to leave, to be renewed, to be relieved.

We would do so again. Before the afternoon was through.

As if she was thinking out loud, I heard her say that she only hoped for the least volatile version of the various dystopias she’d imagined. We agreed that we could live in the bush longer than most. I know a few rarely visited spots where I could shelter without too much nuisance, for a while; I vowed that I would show her, if push came to shove. I let a thought silently pass by – this should not be a normal conversation. Why am I now thinking about matters of basic survival every day?

The mobility on which we had both hinged our lives, we had to admit, relied on an archaic method anyway: refined petroleum. That exotic product promised freedom, but a side-effect was the carbon emitted in the wake of our vehicles. The independence was an illusion. If, say, missiles are fired in the Strait of Hormuz, I may not be able to afford these long drives alone. I can’t extricate myself from the tangle of the global economy. When it all comes a cropper, we’ll go with it.

Later that afternoon I walked her down the driveway and waved goodbye as she turned the Pajero into the sun. “I’ll keep going,” she’d said in announcing her departure. The mountains around me blazed blue, but soon the heat and light would fall out of the day. I had a place to rest my head and stack my books. It was a semblance of home, but one that wouldn’t stay mine. For a while I could rent a little security, but only enough to take a deep breath and steady myself for the next move.

After a night of troubled thoughts, I too went for a drive. I left just on dawn. Pademelons and possums danced in front of me. The back roads were black with dew; they curled through gaps in the grey-green forests. I’d packed a billy, a tent, a sleeping-bag and a few books. I didn’t schedule my return; I had no commitments. Perhaps someday I will look back on all this as folly, as a misevaluation of what was needed. Or maybe I will savour the memory of a brief foray into freedom on open roads, having rejected some contemporary values and shrugged off one or two expectations.

Maybe, if we pulled through, it would seem like it was a great escapade. I would remember a morning in which I had the sun behind me and Bruce Springsteen on the car stereo, as I propelled myself along those overlapping strips of asphalt until I saw the ocean.

. . .

A few weeks later, when it seemed I might be moved on from my rented room, I remembered that talk up at the shack, next to the duck pond. I sent her a text message. I was standing under an awning as it poured with autumn rain, and I mentioned a fisherman’s hovel to which we’d both bushwalked. “You can come and visit me,” I said, “I’ll be living in that hut amongst the alpine yellow gums. Sleeping on a mat like a spinster from a South American novel.”

She replied, “I have been thinking. Maybe this precarity will eventually teach us vulnerability.” I stood under that awning a long while, watching the water sluice down the gutters and fill the river to the top of its banks. My phone beeped again. “Drive safe,” she had added.