Between 1805 and 1808, most of the population of Norfolk Island relocated to Van Diemen’s Land. More than 700 people arrived, suddenly representing more than 20 per cent of the European population and starting a profound relationship between Van Diemen’s Land and Norfolk Island that would see humans transported back and forth for the next five decades.

Imagine Tasmania receiving an influx of people equivalent to 20 per cent of its existing population today. That would be 100,000 people. In such numbers the migrants would be capable of huge influence over the future of Tasmania. The Norfolk Islanders who came early in the 19th century did play a major role in creating the Tasmania we know today.

Norfolk Island is a tiny green dot in the vast Pacific Ocean. It is five kilometres wide and eight kilometres long. The Australian mainland is more than 1,400km away while New Zealand lies more than 1,000km to the east. The vegetation is a confusing fusion of tropical and temperate species. The island’s isolation has created a unique environment with a large number of endemic plant and animal species.

Polynesians settled on Norfolk Island in the 13th century bringing with them some of their favourite food in the banana, and the Polynesian rat. Within a few generations, however, the people had disappeared, leaving the island uninhabited again for centuries. Then in 1788, a few weeks after the First Fleet arrived at Port Jackson, Governor Arthur Phillip despatched Lieutenant Philip King, with a team of 15 convicts and seven free men, to take control of Norfolk Island. Conscious of French exploration in the Pacific, Britain was concerned that Norfolk Island might fall under French control. It was thought that Norfolk Island had great commercial potential with Norfolk pines for ship building and native flax for rope and sail manufacture.

Norfolk Island quickly became even more important to the empire as the new colony in Sydney was having little luck growing crops or hunting game. The colony was beginning to starve. In 1790, to relieve some of the pressure on Sydney, convicts and marines were sent to Norfolk Island, which was to become the food bowl for the Australian colony. Fresh optimism turned to despair when the HMS Sirius was wrecked on the rocky shores of Norfolk Island. Everyone survived, but they were stuck on Norfolk Island for 10 months and unable to assist when the Second Fleet landed at the now wretched colony in Sydney with a cargo of sick convicts.

After much toil, it was discovered that the timber of the Norfolk pine, despite the straight and symmetrical trees, was no good for shipping. The flax was proving difficult to utilise too. In desperation, two Maori men were kidnapped from the coast of New Zealand on the assumption that they would know the skills of preparing flax, only to find when they got them to Norfolk Island that in Maori culture flax was considered women’s work and the two men had no idea.

. . .

These disappointments and the eventual success producing grain and vegetables in Sydney began to create the case for abandoning Norfolk Island. It wasn’t cheap maintaining a remote settlement. In 1803, the Secretary of State, Lord Hobart, called for the removal of most of the Norfolk Island population to Van Diemen’s Land.

The order pre-dated the first permanent colonial settlement in Van Diemen’s Land, at Sullivan’s Cove in in 1804. At this time, it is estimated that there were 5,000 to 10,000 Aborigines on the island. Even in 1807, the white population had only just surpassed 3,000. There were only a few significant colonial settlements in the south and the north and the first overland journey between Hobart and Launceston had only just been completed (taking nine days). This is the world to which the Norfolk Islanders, mostly convict and military families, came.

Most Norfolk Islanders didn’t want to leave. The convict families had enjoyed relative freedom and had worked hard for several years to create a successful little agricultural home. They had become attached and proud of their lonely little Pacific island. This is the main reason it took several years to relocate the population.

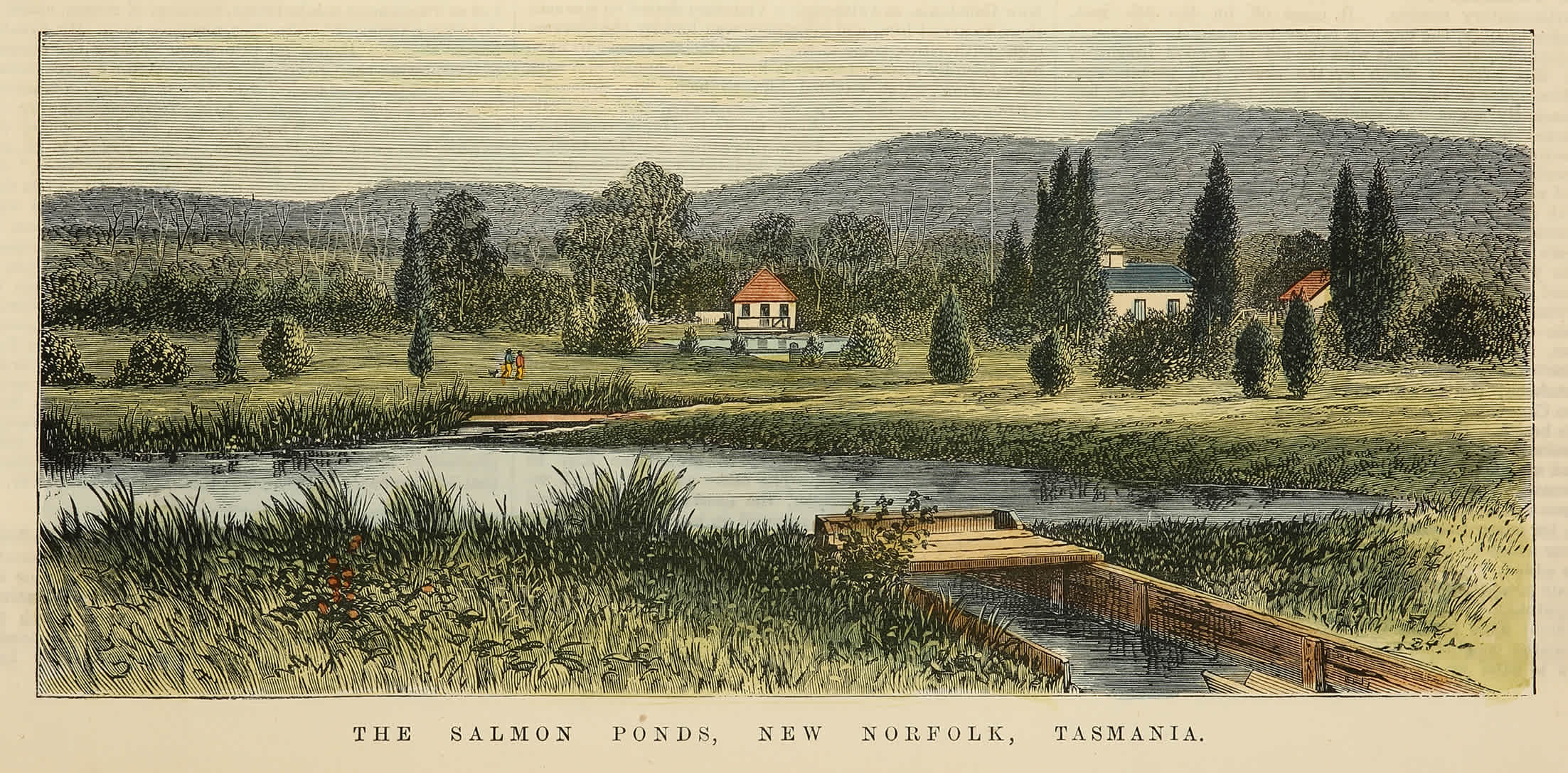

However their “nature-taming” and agricultural skills were thought to be just what the new colony of Van Diemen’s Land needed. The Lady Nelson, the ship that anchored at Risdon Cove in 1803 and first claimed British settlement of Van Diemen’s Land, sailed 2,500 kilometres to Norfolk Island in 1807 and returned with about 160 people. They sailed up the Derwent River, past a rapidly expanding Hobart, to a small settlement called Elizabeth Town, which would soon be renamed New Norfolk in their honour.

Many of these arrivals were First Fleeters who had been sent to Norfolk Island from Sydney in 1788. Ten First Fleeters who came to Van Diemen’s Land via Norfolk Island are buried in the Methodist Chapel at Lawitta, on the outskirts of New Norfolk. One of these ten headstones is that of Betty King, a First Fleet convict girl who married at New Norfolk in January 1810. The headstone reads, “The first white woman to set foot in Australia.” She is also thought to have been the last surviving First Fleeter when she died aged 89 in 1856.

The settlers were offered land grants around New Norfolk as compensation for their relocation and in the hope that they would “civilise” the wilderness to make the land produce, and ultimately supply goods that could be exported or traded. After some early struggles adapting from the sub-tropical conditions of Norfolk Island to the colder climate of the Derwent Valley, the area became a productive region for sheep, cattle and various crops.

This relocation of Norfolk Islanders to Van Diemen’s Land continued until 1814. Longford, in the north of Tasmania, like New Norfolk expanded and became a significant town in large part due to the resettlement of Norfolk Islanders. Governor Macquarie granted them land rights near Longford and they quickly named the area Norfolk Plains. Another large group of Norfolk Islanders was transported to Port Dalrymple on the Tamar River, about where George Town stands today.

After the last person left Norfolk Island in 1814, the island rested, peacefully abandoned, until 1825 when the British government decided it should be occupied once again. Norfolk Island’s isolation, previously leading to its downfall as a colony, was this time seen as its advantage. It was to house “the worst description of convicts”, recidivists and those who were to be denied any hope of ever living a free life.

The dark days of the relationship between Tasmania and Norfolk Island had begun.

. . .

With the large number of former Norfolk Islanders living in Van Diemen’s Land at the time, there must have been quite a strong knowledge of the island amongst the population and, given the different circumstances of the first British colonisation and the reluctance with which many left, it would have often been described with fondness and longing. But this second colonisation was not a new start, it was about punishment. It was to be a hell in paradise.

Van Diemen's Land’s Governor Arthur believed that: “When prisoners are sent to Norfolk Island, they should on no account be permitted to return. Transportation thither should be considered as the ultimate limit and a punishment short only of death.”

So it was that Van Diemen’s Land would send those who were to be denied even hope, to the Pacific island where so many of its successful early settlers had so hopefully wanted to remain.

Tasmania’s most famous bushranger, Martin Cash, twice escaped the “inescapable” Port Arthur before being found guilty of murder. He was sentenced to death by hanging, but in a last-minute reprieve he was sentenced to life on Norfolk Island instead. He didn’t lose hope, eventually becoming a constable on the island before marrying and returning to Tasmania and becoming overseer of the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens, amongst other things. He died of old age in Glenorchy.

James Porter, who in 1834 famously stole the brig Frederick with nine other convicts and sailed from Sarah Island, out through Macquarie Harbour and across the Pacific to Chile, was also sent to Norfolk Island after he was eventually caught in Valdivia.

Norfolk Island was under the jurisdiction of Van Diemen’s Land from 1844 to 1856. In part due to growing exposure in London of the brutality of the penal settlement at Norfolk Island, it began to be wound down in 1847. From then until, until the settlement was finally closed in 1856, another stream of Norfolk Islanders arrived in Van Diemen’s Land. This time, however, the arrivals consisted only of male convicts, rather than a mix of free and convict families.

That year, 1856, was a big one for Van Diemen’s Land – after receiving 75,000 convicts (more than 40 per cent of all those sent to Australia) transportation ceased, the island was granted self-government, and its name was changed to Tasmania.

. . .

One can’t help but wonder if Norfolk Island might have become a sub-tropical miniature Tasmania had it remained part of the jurisdiction of Van Diemen’s Land after the penal colony was abandoned in 1856. As it happened, later that year, another different ethnic group arrived to a once again uninhabited Norfolk Island to make it their home. They came in a ship from Pitcairn Island, 194 people, the vast majority being descendants of the Bounty mutineers and their Polynesian wives. Today, 45 per cent of Norfolk Islanders are directly descended from the original eight Pitcairn families aboard that ship.

In 2015, it is easy to see parallels between Norfolk Island and Tasmania. The remains of the penal settlement at Kingston are so surreally reminiscent of Port Arthur. There is a feel to these 19th century convict settlements that I think is shared. Like Tasmania, the influence of Britain on Norfolk Island is inescapable and is most visible in the architecture, gardens, introduced species and culture.

Tasmania and Norfolk Island face similar economic challenges inherent to small populations and isolation. Tasmanians today talk of being the food bowl that Norfolk Island was once to be. Both islands are increasingly exploiting the opportunities of tourism, particularly by offering experiences based around the natural environment, history and culture. There is still much potential for the two islands to be learning from one another.

A large proportion of Tasmania’s early European settlers learnt their agricultural skills and became accustomed to the strange environments of the Southern Hemisphere on Norfolk Island. Most of the people who formed the first British settlement on Norfolk Island had not originally been farmers, known how to fish or build when they were transported, but by the time they left to resettle in Van Diemen’s Land many of them were very capable, and were relishing their new life and the opportunities of their new world.

The environment shapes people, particularly when they must have a close and dependent relationship with it, and it was Norfolk Island’s environment that shaped a large proportion of Tasmania’s earliest settlers.

A publisher once told James that when he is asked for his bio, he should say: “James writes subversive essays about important things.” James felt a bit awkward about saying this publicly, but secretly he liked it. He has written for many publications. His books are Essays from Near and Far, Walleah Press, 2014 and The Balfour Correspondent, Bob Brown Foundation, 2017.

This article was first published in Issue 79 of Forty South print magazine.