WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are warned that this story contains images of deceased persons.

I’m sitting on a bench in a large room with deep blue walls. The colour reminds me of a Tasmanian sky at dusk, a sky that would have been noticed by countless Aboriginal people over thousands of years, perhaps when they gathered to eat what is now considered gourmet food – oysters and abalone fresh from the sea, wild cherries, or char-grilled wallaby.

I am looking at portraits of some of these Aboriginals, done soon after colonisation. They show a rapid loss of the freedom to enjoy these fundamental pleasures.

The paintings hang in a long line on the blue walls in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Sophisticated lighting makes the small portraits stand out like beacons, the people they portray trapped in their rectangular frames.

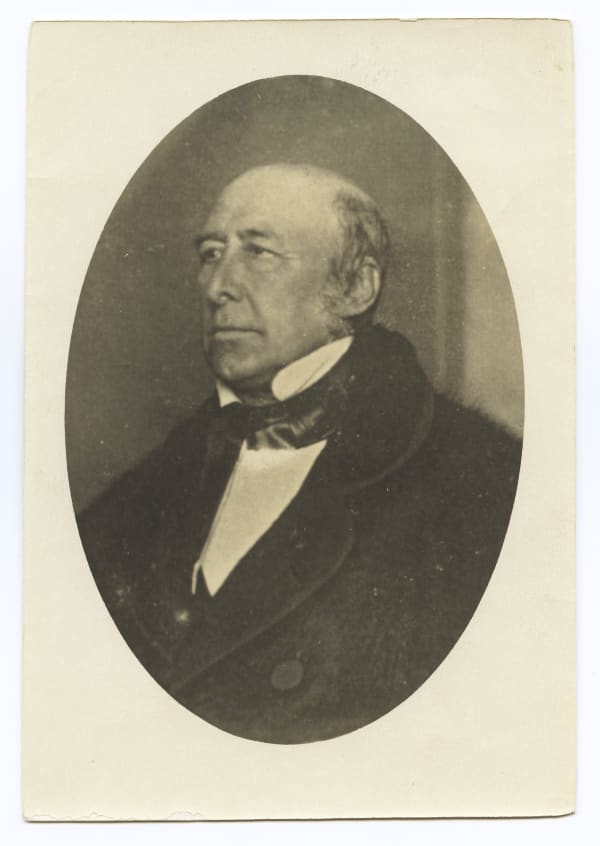

The names applied to these artworks – Trugernanna, Woorrady, Wortabowigee, Manalargenna, Mathinna – are familiar to Tasmanian Aboriginals. For their many descendants, viewing them can be distressing, but it’s probably the only opportunity they will have to see these representations. Painted in Hobart by convict artist Thomas Bock between 1831 and 1842, all except the painting of Mathinna were commissioned by the “conciliator” of Aborigines, George Augustus Robinson, and depict prominent members of tribal groups who were diplomats, mediators and guides for the British invaders.

On a recent visit to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, I saw the finalists in Australia’s contemporary prize for portraiture, the Archibald. The aim of the award is to “perpetuate the memory of great Australians”. I couldn’t help wondering what Bock would have written on the descriptive cards next to his portraits if he had entered them in such a prize. With reference to evidence he probably had at the time, I’ve imagined the card’s content and then, secondly, filled in what is now known of the remainder of the subject’s life. That is, I’ve reframed the paintings in the context of the Archibald Portrait Prize.

Woorrady

The reframe: Woorrady is considered a clever man by his people. He is from Bruny Island, South East Nation. He and his wife, Trugernanna, often act as instructors in language and customs for G.A. Robinson as he seeks to gather remaining Aborigines to Flinders Island. Just as Robinson tells stories of his beliefs, Woorrady is exceedingly knowledgeable about his own culture, his people’s values and Creation. He also tells stories of battles between the Van Diemen’s Land nations, using songs and gestures to act out incidents. His hair and beard, dressed with red ochre, denote his high status and the respect he deserves. The artist has painted his portrait with great care. Robinson is much displeased that he has supplied Lady Franklin with copies.

The background: Wurati met Robinson in 1829. He travelled with him throughout Tasmania for many years, and then to Port Phillip in 1839, where he saw the difficulties that beset Aborigines in Victoria. He missed his Country. He watched the dispossession of his people and, despite his courage and desire to find peace, these experiences were a major factor in his early death on the way to Flinders Island in 1842. He is buried – at the other end of Tasmania from his territory – on Big Green Island, west of Flinders Island.

Trugernanna

The reframe: Trugernanna’s traditional land is around Port Esperance on the western side of the D'Entrecasteaux Channel. She is the daughter of the chief Mangerner, but by the time she was 17 her mother, sister, uncle and intended husband had been killed by Europeans, and she had been abducted. Her desire to end this violence possibly led her to join Robinson and assist him on his travels. She is about 20 in this portrait, and her bearing is serious and proud. The artist has carefully painted her long maireener shell necklace – an indication of her position and identity. She is outspoken and quick to defend her husband and her culture. Mr Bonwick writes that, “Her mind [is] of no ordinary kind. Fertile in expedience, sagacious in council, courageous in difficulty.” If anyone can survive this brutal colony, she will.

The background: Gaye Sculthorpe, an Aboriginal Tasmanian and curator of Oceanic Collections at the British Museum, has uncovered an enduring mistake in Bock’s labelling of a subsequent set of these portraits, where Trucanini’s name is on the painting of Wortabowigee and vice versa. Did Bock fall into the trap of so many Europeans who see people of colour as representative of their race, rather than individuals? Sculthorpe believes the stern gaze Trucanini directs at Bock is an evocation of the terrible events she witnessed. Later she was worried her body would be dissected and analysed by European scientists, as were members of her community at Oyster Cove in the 1830s. She was right: after death her body was acquired by the Royal Society of Tasmania and her skeleton exhibited at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery until 1947.

Wortabowigee

The reframe: Wortabowigee comes from Port Dalrymple on the north coast of Van Diemen’s Land and speaks English well – Robinson says she has not a word of an Aboriginal tongue. She was removed from the sealer Michael Mckenzie in 1830. He had taken her by force to Flinders and Kangaroo Islands where, she says, slave traffic is common – women are bartered or sold by sealers who often beat them. Since their liberation, the women have been very cheerful. Wortabowigee is handsome, of quick intellect and strong. Robinson says she can navigate a schooner, “hand, reef and steer”.

The background: The Aboriginal women who remained on the Bass Strait Islands for multiple generations shared and preserved celebrations and activities, such as mutton birding and shell work. They formed a distinct, ongoing community that is an important part of palawa culture today.

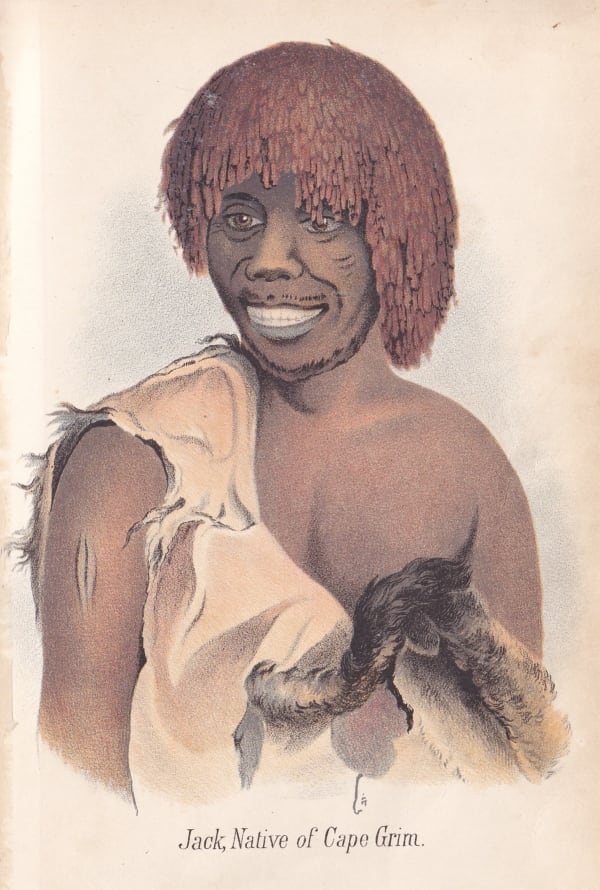

Tunnerminnerwait

The reframe: Tunnerminnerwait is from Cape Grim in the north-west. He is Wortabowigee’s husband. By 1830 most of his nation had been killed by colonists, so he travelled with G.A. Robinson. He seems amused to be in a European house and asked to be still. He prefers the smell of eucalypt leaves, the sound of wind and the taste of wild food, rather than tea. He has a good-natured personality, despite the tragic times his people are going through and the fact that his 40,000 year-old race is being dispossessed of its tribal lands. The publisher, Henry Dowling, who is familiar with many of the people in these paintings, is quoted as saying he can “confidentially speak to the faithfulness of the portraiture”.

The background: Tunnerminnerwait went with Robinson and several others to Port Phillip in Victoria in 1841, where he was convicted of killing two whale-hunters in the Western Port area. He had recently returned from several months gathering evidence with Robinson about a massacre by whale-hunters of between 60 and 200 members of the Gunditjmara clan at Portland He was not allowed to give evidence in court in his own defence. Tunnerminnerwait and another member of the party, Maulboyheenner, were hanged before a crowd of 5,000 people at Melbourne’s first execution in 1842. Judge John Walpole Willis said their punishment was designed to inspire “terror... to deter similar transgressions”.

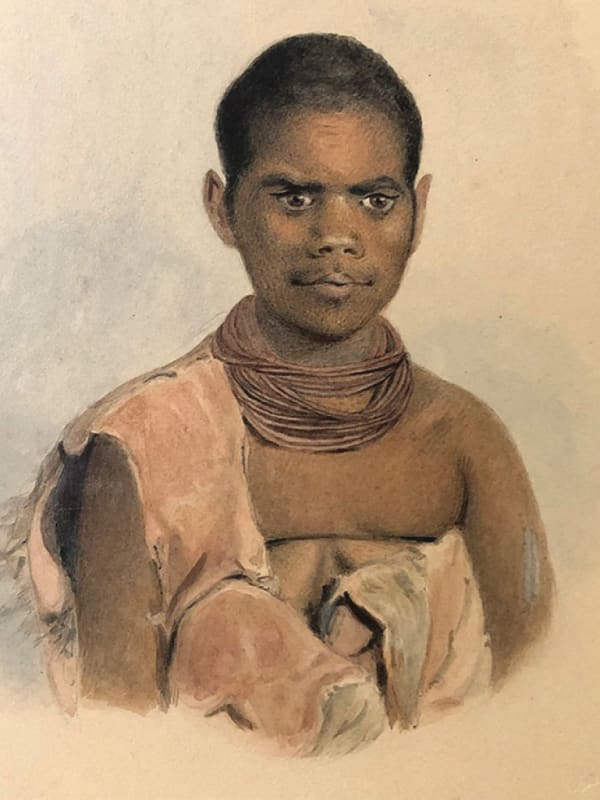

Probelatter

The reframe: This young man’s other names were Larcurkenner, which means “pigeon” in the language of his district, and Lacklay. He is from Hampshire Hills, in the north-west. In the portrait, he carries a spear and wears a kangaroo skin, which is expertly draped around his body. His necklace is twisted animal sinew, which is ochred, as is his hair. He was captured by one of the armed parties when only a boy and continued the traditional practices of his clan, even when on Flinders Island, far from his Country. Robinson says Lacklay found the lair of a hyena with three beautifully marked cubs on the eastern shore of the Derwent near Mr Macpherson’s farm. He has a trusting expression and is an artist too – he has made a sketch of a hen.

The background: Probelatter went with Robinson to Port Phillip in 1841 where he disappeared, believed drowned at Western Port. He was about 21 years old.

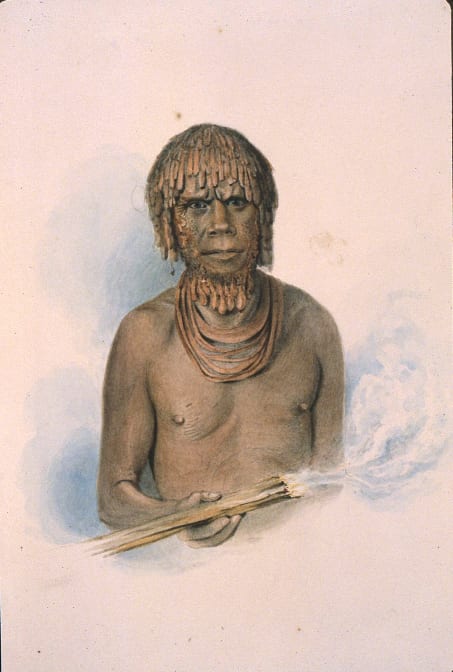

Manalargenna

The reframe: This is the portrait of the powerful leader of the Plangermaireener Nation of north-eastern Tasmania. He led attacks against the invasion of his land, was captured in 1830 and has spent many years with Robinson, acting as negotiator and diplomat in the search for other Aboriginal people. He is a proud man and is said to sharpen his spears to frighten aggressive Aborigines away. He is sometimes impatient with Robinson. His wife, Tanleboueyer, is thought by Mr Duterrau to possess “much dignity of manners”. According to Robinson, during the six years they were with him they never quarrelled. James Backhouse, the Quaker, thinks Manalargenna is a man of fine person and features. In this portrait, which is reported to be “most scrupulously accurate”, he is holding a firestick.

The background: In 1831 Robinson promised Manalargenna that he and his people could return to their ancestral lands but, instead, against his will, he was transported with 133 others to Flinders Island. He died not long after arriving there in 1835. He is the ancestor of many Aboriginal people in the Tasmanian community today.

. . .

History is slippery. There are gaps, ambiguities and multiple perspectives in records for this period, while almost all information is second or third hand and enclosed in white frames. By the time these portraits were painted, the environment around Hobart Town, where the Muwinina people had hunted, eaten meals and performed ceremonies, was a busy colonial settlement. Thomas Bock lived in Campbell Street, where the foundations were soon poured for the Theatre Royal. A few years later, the imposing building in Davey Street, where this exhibition was recently held, was constructed.

So, look at these pictures of people who were so prominent in the history of the island. They are essential viewing to even begin to understand Tasmania’s past, while in the room next door, The National Picture takes Bock’s subjects out of their frames and forces our gaze in another direction: through the prism of the Black War. What eventually happened to the people portrayed exposes the enormity of the crimes against Aboriginal Tasmanians that continues to resonate for their descendants today.

Carol Freeman is researcher and writer who has lived in Hobart for over 30 years. Her work appears in books and academic journals, exhibition catalogues and art magazines on topics that connect art, science and history in innovative and provocative ways. These include a co-edited book Considering Animals: Contemporary Studies in Human-Animal Relations, essays such as Is this Picture Worth a Thousand Words? in Australian Zoologist, catalogue essay Reconstructing the Animal for an exhibition at Tasmanian College of the Arts and book reviews for Historical Records of Australian Science. Her major publication, the book Paper Tiger: How Pictures Shaped the Thylacine, is published by Forty South. Since 2015 she has been a regular contributor to Forty South on a variety of subjects.